The director Joanna Hogg has sounded a warning on the future of arthouse cinema in a call to arms that saw her attack a “certain kind of cinema” for being “homogenised” and lacking passion.

Hogg, whose most recent film, The Souvenir, won a Grand Jury prize at the Sundance film festival, was speaking at a screening in London on Tuesday of a freshly restored silent film, and echoed Martin Scorsese’s recent attacked on superhero films.

“What will happen in a few years, even five years’ time?” she said. “Will I still be able to make films? Will I be able to make films that you can see in a cinema like this? I may have to do something else,” she said. “I think it’s a very serious moment. We have to really be awake to do something about it,” she added.

Hogg was discussing the preservation and restoration work of the Film Foundation, of which she has recently been made a director. “It’s particularly timely to keep thinking about this kind of restoration work when the world of cinema is changing,” she said. “There’s a certain kind of cinema, but I’m not sure if you can call it cinema, that’s very homogenised in a way, that’s not created out of a real passion.”

Hogg’s remarks echoed those of the Film Foundation’s founder Martin Scorsese, who told Empire last month that he considered Marvel movies “not cinema” and then restated his argument in the New York Times.

At the screening, Hogg suggested that stewardship of our cinematic heritage was somewhere between a moral obligation and a gift to future generations. “It would be very selfish of us not to be concerned with our culture and think of the future. It just seems incredibly careless of us not to look after an art form that’s still so young.”

Ninety per cent of silent films had been lost, she added, saying: “Could we imagine not being able to read War and Peace? That we couldn’t get hold of a copy, it’s unimaginable. Or say there’s a Caravaggio that is falling apart, that’s fading, that needs work, that we would discard it? That we wouldn’t actually work to restore it?”

Hogg spoke about how she was inspired to become a film director after watching classic movies on TV as a child (“I was known as square eyes”) and also by seeing arthouse cinema in London as an adult.

Commentators defended Scorsese by pointing both to the work of the Film Foundation and his support of younger film-makers to demonstrate that he is actively involved in the cinema beyond his own work.

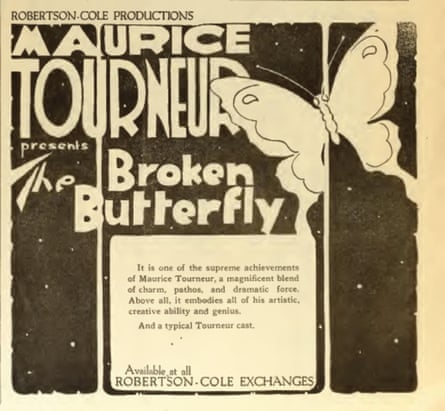

The film shown at the screening, Maurice Tourneur’s 1919 drama The Broken Butterfly, was a prime candidate for a benevolent restoration – each scene picturesquely framed and delicately lit, with soft tints and illustrated intertitles. It is a poignant romantic melodrama whose plot has some jaw-dropping moments. Its now little-known stars, Pauline Starke and Lew Cody, give intensely serious performances. Hogg told the audience that the film had moved her to tears and that she had “goosebumps everywhere” while watching it.

Scorsese suggested the film as a candidate for restoration – as a little-known work by a pivotal silent-era director. Tourneur was born in Paris in 1876, and began and ended his film career in France, but for several years in the 1910s and 1920s worked in the US film industry, during which time he made The Broken Butterfly.

His most famous Hollywood films include the epic The Last of the Mohicans (1920) and The Poor Little Rich Girl (1917), starring Mary Pickford. His cinematic legacy includes not just his own movies, but those of his son, Jacques Tourneur, who who became a Hollywood director, making the film noir Out of the Past (1947) and cult favourites such as Cat People (1942).

The Broken Butterfly was restored by the Film Foundation at L’Immagine Ritrovata Laboratory in association with Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé, and was funded by cognac brand Louis XIII. Accompanied by a live improvised score by silent film pianist and composer John Sweeney, the film tells the story of a young woman, raised by a punitive aunt in a Canadian village, who falls in love with a musician who composes a symphony in her honour. As their affair takes a tragic turn, she learns a horrifying secret about her childhood.

The restoration, which has cleaned up the image, reintroduced the title cards, and involved commissioning a new score, has also been screened in the US and France, will be made available online.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion